EMILIA AZCARATE | THE GENEALOGY OF COLOR

Sept. 13, 2019 - Jan. 23, 2020

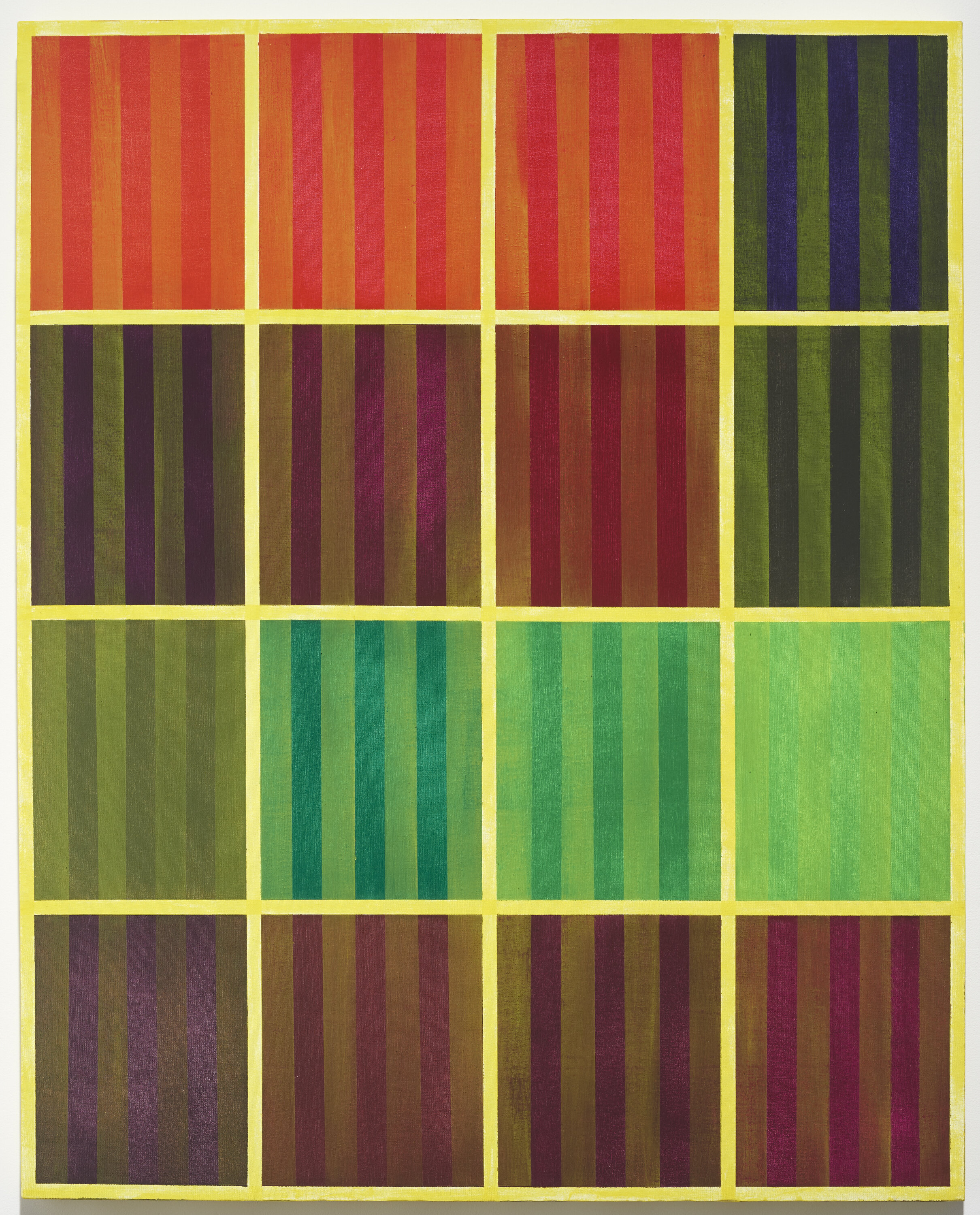

The Genealogy of Color, Emilia Azcárate’s (b. 1964) second solo exhibition in Miami brings together works from Azcárate’s recent series Pinturas de Casta (Caste Paintings, 2015-present), which highlights the artist’s sustained interest in color theory, abstract representation, alphabets and typography, as well as her Latin American heritage. This series is rooted in the ideas of purity and mixture as established through Isaac Newton’s original experiments into the nature of color in the late seventeenth century. In these experiments he refracted sunlight through glass prisms and noted how the colors red-orange-yellow-green-blue-indigo-violet, through being bent (refracted) at different angles, became separated from the original light source (the sun). It is with this understanding of a “natural separation” that Azcárate approaches the genre of the Casta painting–the genre of painting developed by Colonial Spain in order to categorize and hierarchize the new “races”, including Mestizo, Castizo and Mulato, that were being engendered through the marriage and offspring of Spaniards, Indigenous Americans and Africans brought over to the New World as slaves–and attempts to turn it on its head. As Juan Ledezma writes in the exhibition text, “This past is here evoked and then reshaped as its discourse, the colonial statements of racial difference that exercised a spoken violence on mixed identities, is transcribed and transformed—forced out of the context of history and into that of contemporary art, where it will confront a type of abstraction different from its own.”

Azcárate uses the colors pertaining to Newton’s original color wheel–red, blue, yellow, green, cyan and magenta–and assigns a primary color to the three “original races”: red to the Spaniards, yellow to the Indigenous and blue to the Africans, and each resulting “race” coined by the Spaniards represented according to the exact mixture of the original primary colors. As Ledezma continues, “In charting hybridity, the taxonomic terms of analytical knowledge engaged the interracial condition as a quantifiable dimension, and not as a quality imprinted on concrete experience. And in so abstracting the lived reality of the Spanish colonies, knowledge was able to inscribe ethnic divergence within a system of social stratification that ruled the concession of rights in line with unquestionable quotas of privilege.” Azcárate’s works in this series frequently take the linear form of the grid or that of an arborization that denotes the branching out of color mixtures from the trunk of the three primaries. As the original Casta paintings from the eighteenth century featured both a pictorial element and a textual element portraying the intermarriage and resulting offspring of a man and woman from different races and describing the scene with words in an attempt to codify the information and educate the masses, Azcárate’s works too find color fields accompanied with her enigmatic type to signify the arbitrary labeling of the colonial subjects and to symbolize the abstracted disconnect between the signifiers of race and the lived experience of the people upon which these classifications were imposed. Using supports such as a folding screen, artist books, or “codices” as the artist calls them, along with stretched canvases, Azcárate appropriates the traditional symbols of wealth and “[proposes] that colonial discourse be read anew under the terms of abstraction and that Casta paintings be re-perceived from the point of view of our post-colonial present”.

Through the conscious mixing and remixing of colors, Azcárate is also challenging the persistent ideals of purity that are entangled with the enduring societal standards of beauty. In this way, Azcárate demonstrates the beauty in diversity, in the unclassifiable and the not immediately discernible. As Michael Taussig affirms in his essay “What Color is the Sacred?”, “[Color] is not something daubed onto a preexisting shape, filling a form, because colors have their own form.” In this way, color should not be used as a means for separation or denigration but rather experienced as a natural source (light) that, in its many embodiments, has the power to transform, to transport, to revitalize.

Untitled. Tryptich (Mexican School), 2017-2018

Acrylic on canvas. Three panels, 76 3/4 x 39 1/4 in. (195 x 100 cm) each

Untitled (Cristobal Lozano Series), 2016

Acrylic on canvas

20 paintings. 19 5/8 x 31 3/8 in. (50 x 80 cm) each

Untitled (Andrés de Islas Series), 2016

Polyurethane on aluminum. 48 x 59 in. (122 x 150 cm)

Untitled, 2018

Acrylic on canvas. 39 1/4 x 31 3/8 in. (100 x 80 cm)

Untitled, 2018

Acrylic on canvas. 39 1/4 x 31 3/8 in. (100 x 80 cm)

Untitled, 2018

Acrylic on canvas. 39 1/4 x 31 3/8 in. (100 x 80 cm)

LIBRO PERU

Gallery views