“A piece of cloth, a tapestry, or any other fabric obeys a unique "syntax", in the same way, that a story follows a specific "structure". In the end, it's all part of the same Trama whether it has been woven with threads or words.”

— Félix Suazo

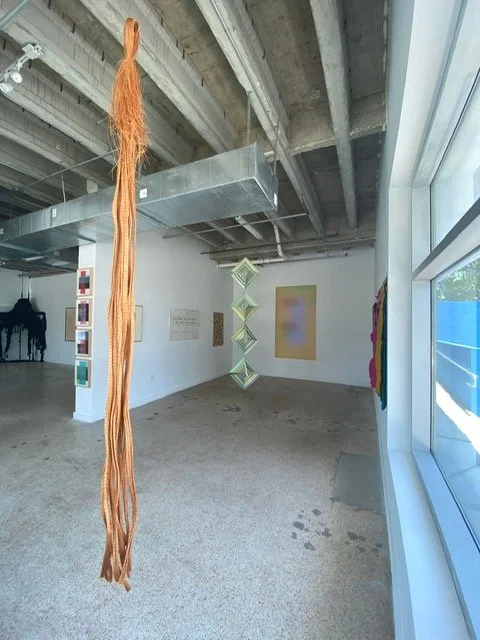

TRAMA | structures, entanglements, and loose ends.

May 26th to September 26th 2022

META Miami and Henrique Faria New York are pleased to present TRAMA, structures, entanglements, and loose ends.

Everything that exists, even that which is unknown, is linked together on a web. This link, not always visible, weaves planets, ideas, and dreams, connecting them in the same sphere. From that point on stems a principle of unity that holds together the structure of the universe; from a fragile spiderweb to the intricate geometry of an astronomical chart.

Beyond this ambitious hyperbole, however, the term Trama poses a more modest and ambivalent question, one that relates to both textiles and the plot of a story. Both actions —sewing and narrating— are one and the same. A piece of cloth, a tapestry, or any other fabric obeys a unique "syntax", in the same way, that a story follows a specific "structure". In the end, it's all part of the same Trama whether it has been woven with threads or words.

In addition to its literary connotation, Trama is an ancient and multifunctional disguise that links, splices, and ties together other human activities. It is woven in “counter-thread” for the seamstress, “net” for the fisherman, “bars” for the prisoner, “screen” for the mason, “veil” for the widow, “safety net” for the acrobat, “fence” for the intruder and “sieve” for the baker. Similarly, Trama can be synonymous with "mesh" in screen printing, "structure" in architecture and urban planning, "grid" in design and advertising, and "pattern" of horizontal lines in television and electronics.

Given the sheer number of meanings, one should not forget that etymologically, the word Trama is also the connecting point for oral and written stories, that organize everyday events and give meaning to human actions in the construction of the story.

It is thus no surprise that the idea of an interconnected universe has become a subject of study and the central theme for the works featured in Trama, this exhibition organized by Meta Miami and Henrique Faria, New York. The show brings together installations, sculptures, paintings, and drawings by a group of 24 artists from Central and South America, whose approaches refer to the fields of literature and textiles. They originate from countries such as Argentina, Colombia, Guatemala, Cuba, Mexico, Peru, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela, where the traditional and the contemporary coexist in constant debate, creating very diverse and complex patterns.

Geometry, materiality, and space frame the physical coordinates among which several of these artworks are developed. The reticuláreas of Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt, Hamburg 1912 - Caracas, 1994), the cuadrículas of Eugenio Espinoza (San Juan de los Morros, 1950) and the rejillas of Sigfredo Chacón (Caracas, 1950) present a bridge between the specificity of the modern canon and the broader contemporary expectations. Along the same line, Pedro Tagliafico(Caracas, 1944)interplays geometry and folding in his various approaches.

The string works by Milton Becerra (Táchira, 1951) follow a mandala-like pattern determined by radiating lines and intersecting points. Diana de Solares’ (Guatemala, 1952) hand-dyed shoestring works focus on the relationship between structure and place. On the other hand, Lisu Vega (Miami, 1980), presents her textile works in a tentacle-like format following an irregular modulation to accentuate differing spaces and volumes. All of these artists deal with space, either limiting themselves within the perimeter or extending beyond.

Bridging the ancestral and the contemporary, Cristina Colichón (Peru, 1967), Emilio Chapela (Mexico, 1968), and Alberto Casari (Lima, 1965), use textiles to explore ideas related to art, ecology, and spirituality. Meanwhile, Álvaro Gómez (Bogotá, 1956) sheds new light on traditional weaving techniques using geometry, relief, and weightlessness while Ella Krebs (Peru, 1926) incorporates pre-Columbian references and symbolism in her "fibrostructures".

Usually, the spoken or written word defines what is visible. Horacio Zabala (Buenos Aires, 1943) treats writing as a self-reflexive manifesto. For Alessandro Balteo-Yazbeck(Caracas, 1972), texts and images refer to the complex link that exists between a document and its place in history. For his part, Ramsés Larzábal (Havana, 1966) combines materials and words in his textile works.

Every once in a while, things go astray or something breaks. The spreadsheets drawn by Johanna Calle(Bogotá, 1965) and the girl outlined on graph paper by Diana López (Philadelphia, 1968) demonstrate this rupture, which can be playful or dramatic, depending on the respective approach of the artist. There are even greater disruptions such as the one recreated in the faded and frayed flags of Juan José Olavarría (Valencia, 1969), who approaches the work as a ritual of symbolic cleansing.

There is an invisible thread that intertwines the personal universe and human cosmogonies. Emilia Azcárate (Caracas, 1964) uses the dot as a unit for recording energetic and spiritual processes. For Héctor Fuenmayor (Caracas, 1949) the dotted grid summarizes a part of his spiritual meditations. Mercedes Elena González (Caracas, 1952) combines the psychic, the cartographic, and the astronomical in her neurohilados.

Nothing can resist the passage of time. Everything —even discarded matter— has a place in the fabric of everyday existence. Jesús "Bubu" Negrón (Puerto Rico, 1975) rearranges paper recovered from cigarette butts into abstract patterns. Pepe López (José Luis López-Reus, Caracas, 1966) creates geometric compositions with recycled and sewn plastic bags. Esvin Alarcón Lam (Guatemala, 1988) offers a personal view of abstraction based on the appropriation of discarded elements.

As can be seen in the exhibition Trama, the diversity of visual practices that use fabric as a medium or refer to its meanings can be overwhelming. The threads of this visual framework follow a sinuous route whose material and symbolic outcome is not exempt from entanglements and loose ends. Just like in literature, movies and soap operas, the plot can get complicated or confusing.

The certainty that everything is connected does not mean that the structure of this giant network is always visible. The puppet does not see the strings that control its will, nor does the fish know who pulls the line at the decisive moment. One´s vision can only cover a limited spectrum of what exists and the rest is part of a subplot of explanations, reasons, and purposes. After all, one thing is the underlying structure (Trama) and the other is the perceived image.

Félix Suazo

April, 2022

GALLERY VIEWS